|

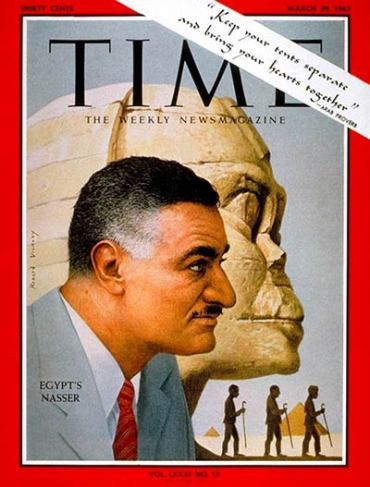

[This is the third article in a series of translations of Egyptian newspapers from the 1960s. To view the other posts, please click on "blog" above.] In 1961, Egyptian movie star Omar Sharif played handsome and sensitive Ibrahim Hamdy, an unlikely resistance fighter on the run, in the hit film في بيتنا رجل, There's a Man in Our House.  Book cover of Ihsan Abdel Quddous' "There's a Man in Our House", 1954. Book cover of Ihsan Abdel Quddous' "There's a Man in Our House", 1954. The film is set before the Egyptian revolution, when Egyptians were suffering under British occupation. After escaping from prison, Ibrahim takes refuge in the last place the police would think to find him: the home of his shy, nerdy classmate, where he lives with his parents and two sisters. As the completely apolitical family gets unwillingly embroiled in the brutal crackdown of any and all dissenters to British rule, they are radicalized by the experience and come out of it genuine nationalists. One of the sisters falls in love with Ibrahim, who dies attacking a military base at the end of the film. The film - dramatic details aside - is based on a true story. It was an adaptation of a 1954 novel by Ihsan Abdel Quddous, who retold the story he received in letters from the real-life Ibrahim, a man named Hussein Tawfik. Tawfik assassinated an Egyptian ally of the occupation, Amin Othman, in 1946. In the book as in the film, Ibrahim dies a martyr for the cause of liberation. But the real-life Hussein Tawfik fled the country after his escape from prison, returned to Egypt after the revolution, and was very much alive when Omar Sharif played him onscreen. I knew all of this before I picked up this newspaper from January 1966, which is why it surprised me to see an article about "the Hussein Tawfik case". Just five years after being portrayed as a hero in a hit film, Tawfik was in prison, and the state-owned press was portraying him as a self-aggrandizing "wicked person" and an enemy of the revolution. What happened? Hussein Tawfik, or the real-life Ibrahim HamdyIt's interesting to note that there is not even a Wikipedia page for the real-life person at the center of this story. Even the Arabic pages for the book and the film about his life doesn't mention his name. So who was the real person behind this famous story? And why has his real life been left out of so many sources, even while some call him the "most famous political killer in Egyptian history"? According to the sources available on the internet, Tawfik's life (1925-1983) was even more eventful than what was portrayed in the short timeframe of the book and movie about him. But he also had a drastically different personality. If you've read the book, you know the great lengths Abdel Quddous goes to to portray "Ibrahim" as a shy, modest character. For example:

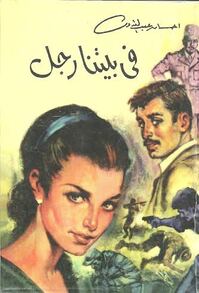

Hussein Tawfik, date unknown. Hussein Tawfik, date unknown. It's my guess that this is a description of the fictional Ibrahim more than it is of the real-life Hussein Tawfik. The first clue is that Tawfik was not an unaffiliated assassin without specific political allegiances as he's portrayed fictionally. According to the best sources I can find online, Tawfik did found his own secret society, but it may have been affiliated either with the Egyptian monarchy or with Egyptian Nazis/fascists. (The Third Reich ran a rather successful propaganda campaign in countries occupied by British forces.) The Muslim Brotherhood also may have helped him flee the country. The second insight into Tawfik's real personality is his lifelong tendency towards grandiose operations which he personally took credit for. It's worth noting that Tawfik wrote to a well-known novelist shortly after leaving Egypt, perhaps in the hope that his story would become even more famous. Once arriving in Syria, he quickly pivoted from his supposed devotion to Egypt to trying to attacking synagogues and trying to assassinate de facto Syrian head of state Adib Shishakli. He may have joined the Arab Nationalist Movement (ALM). Was Tawfik really a nationalist, or was he some sort of terrorist-for-hire? What's clear is that after attempting to assassinate Adib Shishakli in 1950, Tawfik was arrested and put on death row. But he again evaded punishment when Gamal Abdel Nasser took over Egypt in the 23 July Revolution / Free Officers Revolution of 1952. Nasser allowed Tawfik to return to Egypt as a free man. Tawfik's affiliation with Anwar Sadat Anwar Sadat in 1936 (age 18) Anwar Sadat in 1936 (age 18) Many books have been written on the life of Egyptian president Anwar Sadat, perhaps best known for signing the 1979 peace treaty with Israel. Suffice it to say that Sadat's reputation as a normalizer or moderate belies his past as a member of a number of nationalist and extremist organizations in Egypt. In fact, "Sadat was active in many political movements, including the Muslim Brotherhood, the fascist Young Egypt, the pro-palace Iron Guard, and a secret military group called the Free Officers, which sought to liberate Egypt from British influence." Tawfik met Sadat, seven years his senior, when he had just begun his political activities. Sadat may have acted as a mentor toward Tawfik and they worked together in more than one secret society. The first chapter of Ihsan Abdel Quddous' novel seems to relate the story of Tawfik's relationship with Sadat relatively accurately (apart from portraying them as close in age):

Sadat helped Tawfik assassinate the pro-occupation minister Amin Othman in 1946 - the action that set off the story portrayed in the book and movie. In fact, Sadat was arrested along with Tawfik, who was much more famous at the time for personally firing the bullets that killed Othman. Sadat, however, was found innocent, while Tawfik was imprisoned. We will come back to Sadat later, after my translation of the article. Tawfik back home in EgyptIt's no surprise that since one of the leaders of the 1952 revolution had helped Tawfik commit the crime he had run away from, he was allowed to come back home as a free man. Not much is available in sources about the next decade or so of Tawfik's life. However, the article I'm about to translate gives some rare insight: apparently he was given a job in the bureaucracy, got married and had five children. In 1954 the popular novel based on his life was published, and in 1961 Egypt's most famous actor portrayed him as a hopeless romantic with an unshakable commitment to the revolution (lower-case "r" - the film is set before 1952, but the implication is Ibrahim's commitment to the same cause). One would think that having barely escaped prison time for a decade of militant activity in multiple countries, Tawfik would settle down. But it seems Tawfik was not satisfied, and soon landed back in prison. "The Hussein Tawfik case"Let's finally get to the reason that by the time of the 1966 newspaper I'm translating, Hussein Tawfik was a reviled criminal. In 1965, the national security service in Egypt uncovered a new secret society aiming to assassinate Gamal Abdel Nasser himself for allowing Sudan to gain independence. At its head was Tawfik. Once in prison, the ostensibly steadfast Tawfik ratted out enough of his comrades that the number of defendants in the case grew to 14, including members of his own family. (Remember that torturing prisoners was commonplace.) We finally make it to January 28, 1966. On the third page is this article, detailing the defense arguments for Defendant Number 14, the final defendant and Tawfik's father's cousin. My translation follows. Following session lasting half an hour, lawyers conclude their arguments in Hussein Tawfik case Hussein Tawfik delighted to be in trial dock because all television cameras fixed on him: defense Yesterday’s session was short, lasting half an hour, and all lawyers for the accused in the Hussein Tawfik case concluded their arguments while the court decided to adjourn until Saturday for the public prosecution’s representatives to plead their case. The session was chaired by Muhammad Fuad al-Degwy, and the prosecution was represented by Attorney-General Abdel Salam Hamed and state security prosecutor Hassan Gomaa. Two of the lawyers for the final defendant, Muhammad Yusef, made their arguments, and the third, Yusef’s brother-in-law, indicated his agreement with the other lawyers’ statements. The courtroom was packed with the defendants’ wives and relatives. The first to appear was Zakaria Salah al-Abd’s wife, who sat beside the trial dock speaking with her husband until the opening of the session. The following is what occurred at the trial: Chairman – Defense for Defendant 14, Muhammad Yusef. Lawyer – Hussein Abdel Rahman on his behalf. In the name of God and in the name of the blessed revolution[1] that has brought Arab unity to the fore. This question may arise[2] today: is today’s case one of opinion or thought? No. The case is one of corruption of opinion, and deception of thought; opinion and thought have been settled in our republic, and any departure from it is a departure from the consensus and a deviation from what is right. Our country is no longer the downtrodden country it was before the shining light of 23 July, when a new and glorious era began. As we’re on our way to a better life, “If a wicked person comes to you with any news, ascertain the truth”[3]. And who is a more wicked person than someone who renounces his patriotism and goes against Shariah? That would be the prime witness, Hussein Tawfik. The public prosecution has accused the defendant, Muhammad Yusef, of knowing of the plan to attempt a coup and of failing to report it to the prosecution. The prosecution has also said that it is requesting sentencing of the defendants under Article 96, not 87, as established in the minutes of the January 13 session. This means that the prosecution has excluded this Article and the charge of attempting to overthrow the regime no longer applies to the defendants. So, how can Muhammad Yusef be punished on the basis of knowing of the crime which the prosecution has excluded for the rest of the defendants because it cannot be established for any of them? If the prosecution, after long investigation, has excluded this charge, then how can Muhammad Yusef have known of this crime, from his first meeting with Hussein Tawfik, and failed to report it? Abdel Salam Hamed – We presented the charge that he knew of the plan to commit a crime, not that he knew of the coup attempt… Lawyer – This plan, whether a crime or not – and the plan was not a crime, and therefore whoever knew of it and didn’t report it cannot be punished. The point of reporting is that it’s a right by default, but it’s a right qualified by that the report should be about a punishable crime, not about a lawful, unpunishable act. Therefore, I request the complete exclusion of the final defendant from this charge. If we assume that he should have reported something, what was there to report, and what did Hussein Tawfik say to him for him to report it? Hussein’s father is Muhammad Yusef’s cousin. Hussein has been a deviant with an overactive imagination since he was a child, aspiring to fanciful heroics, babbling nonstop, only liking to talk about his escapades. According to Hussein’s brother Saeed, Muhammad Yusef always rebukes Hussein for what he does and how much he talks. When asked, Saeed said, “Muhammad Yusef is our relative, he’s over 70 years old, and none of us ever talked about the organization in front of him. It’d be ridiculous for us to talk about it in front of him – he’d always tell us, ‘You’re the reason your father died.’ It’d be ridiculous for us to talk in front of him because he was an important general for the political police, and he knew more about Hussein Tawfik than anyone, but Hussein never said that Muhammad Yusef knew about the organization. The last time I saw Muhammad Yusef, Hussein was there, sitting with Siyuf talking about his escapades in Syria[4], and Muhammad said ‘Guys, I’ve never agreed with what he’s done – his dad died because of this.’ This Hussein Tawfik person has accused us because he’s the witness, and all he cares about is showing off that he’s a hero even in the toughest situations. When he was questioned in the first interrogation, he started bragging about his 25-year history, that had nothing to do with the charge, starting from 1942 when he was a high school student and started the formation of a secret organization. ‘I killed 3 Englishmen and Amin Othman myself, and in the Shishakli days I formed a secret organization to unite the Arab world.’”[5] Delighted Now he’s in the trial dock, delighted because all the television cameras are fixed on him and he’s on the front pages of the newspapers.[6] Chairman – He doesn’t look it. Lawyer – I’ve been watching him constantly during recess and I’ve found a much more relaxed person than he is now… He’s conceited, he loves the limelight. In his statements against Muhammad Yusef, he said that he was so ancient that he must be in touch with the old era[7] and people from back then, who of course want to bring back the old times. These are his statements, from his point of view, not Muhammad’s Yusef’s, who served the state within the limits of his role with the political police. The question is, why did Hussein bring Muhammad Yusef’s name into this case? In my opinion, Hussein was in Sudan in 1947[8], and Muhammad Yusef was in contact with him in Sudan, as he went there often, and he saw what a bad situation Hussein was in there. So he contacted Hussein Tawfik’s father and asked him to stop helping him financially. It’s possible that Hussein wanted to mention Muhammad Yusef’s name to show that people like Muhammad Yusef were in his organization. And it’s possible that Hussein wanted to benefit from the ruling that by giving names of his partners he would reduce his sentence. Even so, Muhammad Yusef couldn’t have imagined that Hussein, who the revolution saved from Mezzeh Prison[9] and pardoned and put in a center and gave a salary that someone with a PhD couldn’t dream of – he couldn’t have imagined that Hussein was working against the revolution after all that, and after he’d become a father to five children and a husband, the sole breadwinner for his family. Muhammad Yusef served his country for 33 years and oversaw security procedures in the Palestine War against the Zionist activity that gave birth to the Arab league[10]. Does it make sense for him to stand with Hussein and the Brotherhood[11] when he was the first to warn of the danger of the Brotherhood, when he was stable in life, when his daughters were getting married and his sons were studying, when he had turned 67 – why would he join a conspiracy? This is ridiculous. Chairman – Mr. Muhammad Subh, delegate of defendant Muhammad Yusef. Lawyer – The defendant, Hussein Tawfik, thought that Muhammad Yusef hated this new era, because he had been working for the old guard. Muhammad Yusef responded to that in his statements, saying that he had retired, the state had permitted him to travel, his situation was stable, and he had no goals other than stability. The law prohibits punishment of relatives in some cases, and Muhammad Yusef is a relative of Hussein Tawfik. The wisdom of the legislature to pardon them is relevant because of the familial tie which prevents Muhammad Yusef from reporting him. His position was that of a father. He advised him not to do anything wrong, because there was no more room for that or reasons for acting this way, although he still had solidarity. Chairman – Does he mean solidarity in corruption before the revolution, which Muhammad Yusef mentioned when he said that at first there were different parties, but solidarity in corruption? Lawyer – Muhammad Yusef said that, and Defendant 1 misunderstood, his thoughts go in strange directions. I call for acquittal. Chairman – Mr. Halboun. Halboun – I agree with the plea. Chairman – With that, the defense arguments are concluded, and the session is adjourned until 10 o’clock Saturday to hear the prosecution’s arguments. [1] The revolution of 23 July 1952, also known as the Free Officers’ Revolution in English, led by Gamal Abdel Nasser and other military officers, which established independent, socialist, Arab nationalist military rule in Egypt. [2] A play on words, as the word “revolution” and “arise” (i.e. rise up) are linguistically similar in Arabic. [3] Quran 49:6, Trans. Yusuf Ali [4] As mentioned above, Tawfik escaped to Syria and resumed militant activity there. [5] Unclear where Saeed’s quote ends, as the end quote is missing in the text. Remember that Tawfik attempted to assassinate Shishakli, but he was part of an established organization, the Arab Nationalist Movement, not his own secret society. [6] This article is perhaps strategically placed on page 3. [7] I.e., the monarchy which was overthrown in the 1952 revolution. [8] This is not established in any online sources, which say that Tawfik escaped directly to Syria in 1947 or 1948. [9] Now-defunct Damascus prison which held political prisoners after the 1949 coup in Syria, presumably where Tawfik was incarcerated. [10] The War of 1948, in which Egypt and other Arab countries attacked the newly-declared state of Israel after months of ethnic cleansing of Palestinians by Zionist militias. The wording is unclear, but the lawyer probably meant that the fight against the Zionists led to the expansion of the Arab League in 1945. [11] The Muslim Brotherhood, the largest and most significant Islamic political movement in Egypt and the Middle East, outlawed at the time along with all other political parties. AnalysisThe main point I got from the article above is that the state-owned newspaper that published was more than willing to propagate the vilification of Hussein Tawfik - and that this vilification came from both sides of the trial. Notice how the defense attorney begins his arguments by insulting Tawfik both politically and religiously, before distancing his own client entirely from the primary defendant. Tawfik is also portrayed as ridiculously self-absorbed, talkative, obsessed with his own heroism, and ultimately disloyal to the revolution. It's hard to believe that this person is the same one portrayed about a decade before in a novel and film as selfless, soft-spoken, a reluctant hero setting out to assassinate the خونة , "traitors", of the revolution. Now Tawfik himself is being held up as practically the archetype of the traitor. To those not familiar with Egyptian politics it may be confusing why one accusation of an assassination attempt of an individual (Nasser) would lead to complete ostracization from the revolutionary movement. From our perspective, we may see Tawfik as continuing the revolution, fighting the next unjust regime as he did the last. Egyptian politics did not accept this logic in 1966. Nasser was the embodiment of the revolution. As the lawyer explains, public opinion on the topic is "settled": dissent is no longer necessary or permissible. Such an unyielding view of Nasser's heroism was not only imposed top-down by the state, but supported by most Egyptians; it's hard to compare Nasser's clout to any other political figure, but the closest I can come is JFK for American liberals or Nixon for American conservatives. The added twist is that Nasser was a military dictator with unbridled power to extinguish political opposition and censor the press. A linguistic note: The lawyer repeatedly referred to العهد القديم and العهد الجديد , "the old era" and "the new era", referring to the periods before and after Nasser's revolution. These vague terms sound awkward and overly dramatic in English, so I considered capitalizing them, but I don't know if they were used widely enough to justify their consideration as a proper noun. Thoughts from linguists on this issue are well appreciated. So what happened to Tawfik?Hussein Tawfik was sentenced to life in prison for the crime of attempted assassination of the president in 1966. When Nasser died in 1970, Tawfik's old comrade Anwar Sadat became president, leading some to think Tawfik's release was imminent. But Sadat declined to release his old friend, probably thinking him guilty of trying to thwart the Free Officers Movement which Sadat helped lead. There is virtually no information about how Tawfik fared in prison under Sadat's rule, or the fate of his wife and children. One can assume political prisoners were not likely treated compassionately under a military dictatorship. In 1981, Sadat was assassinated by an Islamist group, and Hosni Mubarak became president, a seat he would occupy until the 2011 revolution. For one reason or another, it was Mubarak who ended up releasing Tawfik from prison at the age of 58 in 1983. Tawfik died at his family home only months after being released. He died young, but far from heroically, after his old comrades had taken over the country and become world famous while he languished in prison. I really hope you've enjoyed this article and that I've done justice to Hussein Tawfik's eventful life. My hope is that he would be remembered as an important figure in his political context, instead of a nameless romantic played by Omar Sharif! Thank you for reading, and please look out for my next post, with more on Nasser... Sources:

https://www.marefa.org/ https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/sadat-and-his-legacy-egypt-and-the-world-1977-1997 https://www.albayan.ae/books/eternal-books/2015-11-27-1.2515531 https://www2.bfi.org.uk/news/egypt-s-revolutions-film https://alwafd.news/ Article from Al Akhbar, January 28, 1966, Page 3

1 Comment

Leave a Reply. |