|

إن كُنْتَ نَبِيَّاً.. خَلِّصْني من هذا السِحْرْ.. منَ هذا الكُفْرْ.. حُبُّكَ كالكُفْرِ.. فطهِّرْني من هذا الكُفْرْ.. If you are a prophet Rid me of this witchcraft Of this blasphemy Your love is like blasphemy… so cleanse me Of this blasphemy - Nizar Qabbani, Risala min Taht al-Ma’ (Letter From Under the Sea) (1970) - full translation by Kevin Moore here https://mepfoundation.tumblr.com/post/100317007203/letter-from-under-the-sea-by-nizar-qabbani “One cannot put forth as a rule for translation that it must think of how the author himself would have written just the same thing in the translator’s tongue… Indeed, what objection can be made if a translator says to the reader: Here I bring you the book as the man would have written it had he written in German; and the reader responds: I am just as obliged to you as if you had brought me the picture of a man the way he would look if his mother had conceived him by a different father?” - Frederich Schleiermacher, On the Different Methods of Translating (1813) trans. Susan Bernofsky Shleiermacher wrote in 1813 about a concept that is still common today: the idea that translators should create a text under the hypothetical condition that it is what the author would write if they were writing in the target language today. He ably rips apart this idea by pointing out that this hypothetical is so impossible that it is meaningless; a writer’s language system is so connected to their culture that it cannot be transplanted through time and space. Here I would like to apply that concept to an excerpt from a Nizar Qabbani poem in which he expresses the pain associated with unwanted love. Qabbani plays with religious concepts, arguably the most culturally specific of all literary devices. In one breath he calls the object of his affection a prophet—such a suggestion pokes at the Islamic rejection of anyone who calls themselves a prophet after Muhammad—and invokes the proscribed practices of sihr (witchcraft) and kufr (disbelief or blasphemy). Returning to the idea that the translator of this poem could produce a text as if Qabbani had written it in English, this poem clearly shows how futile such an effort would be. This imaginary Qabbani would not be able to successfully draw on Islamic concepts that are inextricably linked to the Arabic language. He would suddenly be writing for an audience that had Christian associations with words like prophet, witchcraft, and blasphemy. I think we can assume that Qabbani, as an artist, would never have bothered to produce such a work, as its impact would be wasted on an Anglophone audience. My translation accepts these limitations and does not assume to summon this hypothetical English-writing Qabbani from the ether. Certain choices can be made in an attempt to give the reader the shadow of the impression that an Arab reader would have gotten from the text, like the choice of witchcraft (forbidden or disapproved in many Christian traditions) rather than the more value-neutral magic. (Other translations use spell or enchantment here, which is likewise an excellent choice to associate it with the English idiom of being spellbound by love, but I consider it too positive to reflect the fact that magic is generally regarded as a sin in orthodox Islam.) I am also greatly restricted in my understanding of the impression this would make on his audience because I am not a native speaker of this language, nor have I ever been immersed in the “source culture”. In my opinion, translators should acknowledge their limitations instead of claiming an ability to operate in an impossible hypothetical situation. This small excerpt is enough to illustrate why.

0 Comments

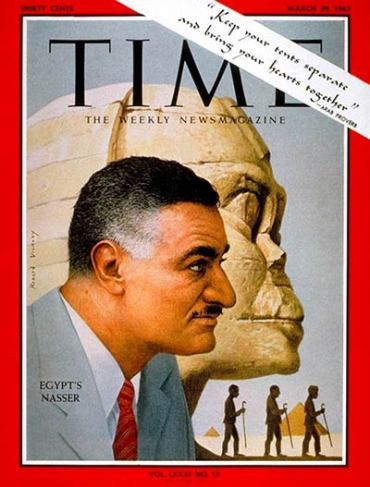

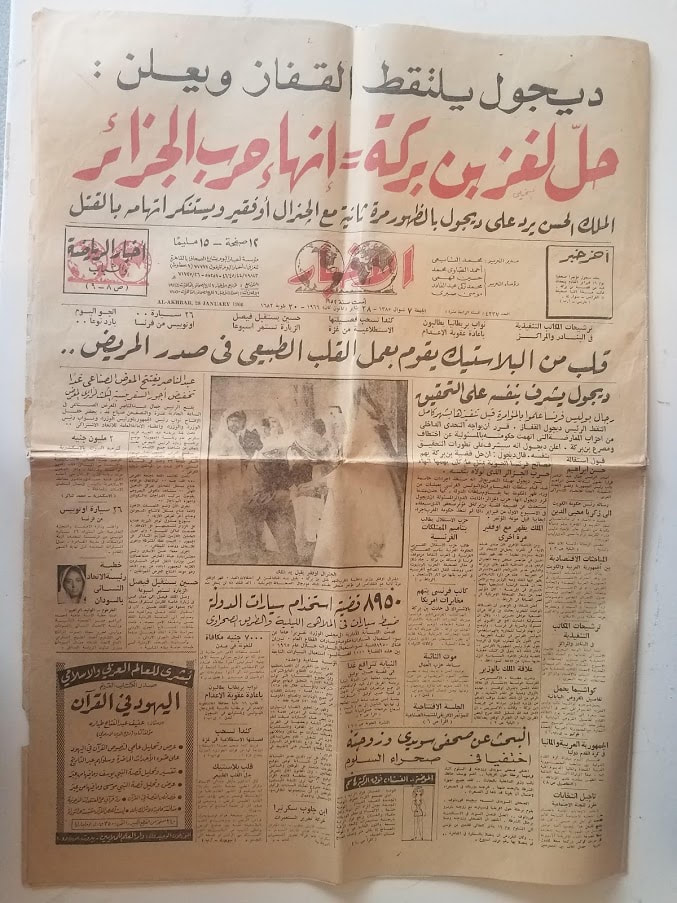

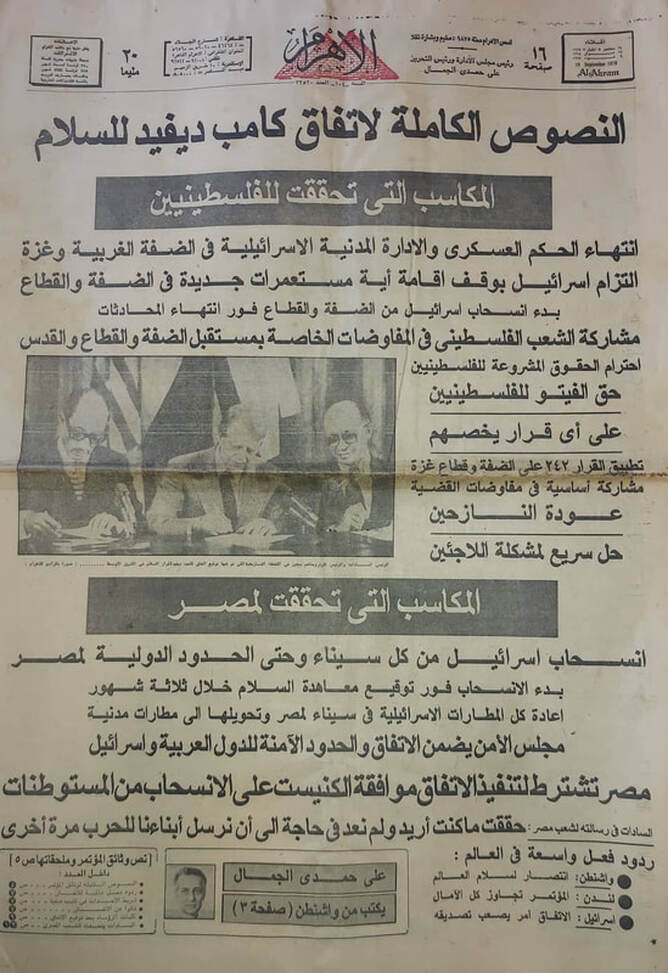

“FULL TEXT OF CAMP DAVID PEACE AGREEMENT” reads the headline of Al-Ahram, the main government-owned newspaper of Egypt, for September 19, 1978. The agreement, known as the Camp David Accords in the United States, had been signed by Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin two days earlier at Camp David. A few days later, Time Magazine would cover the agreement in detail for the US audience in an article titled “A Sudden Vision of Peace: Jimmy Carter stages an extraordinary summit that has old foes embracing”. Camp David is regarded as a pivotal moment in Arab-Israeli relations, as it was the first independent peace treaty between an Arab country and Israel following the 1973 “Yom Kippur War” in which Egypt and Israel had fought for control of the Sinai Peninsula. In the end, Egypt won only a sliver of the Sinai, but, not insignificantly, gained control of the Suez Canal. As a result of the Camp David Accords, Egypt gained control of the entire Sinai Peninsula. However, Palestinians were not included in the talks, and very little was accomplished for those most directly affected by the Israeli occupation and military rule established in 1967.

.Given the probability that significant numbers of Egyptians would be opposed to or ambivalent about this surprise concession to a country long established as their natural enemy, coverage in this state-owned newspaper seems carefully arranged to assuage common concerns. Let us consider the headlines, in order: FULL TEXT OF CAMP DAVID PEACE AGREEMENT GAINS WON FOR PALESTINIANS GAINS WON FOR EGYPT SADAT IN MESSAGE TO EGYPTIAN PEOPLE: I GOT WHAT I WANTED AND WE WILL NOT HAVE TO SEND OUR SONS TO WAR AGAIN Disregarding the other text on the page, these headlines can tell us a lot about the impression the Egyptian government wanted to give Egyptians about the agreements.

I will continue my translation and analysis in separate posts about the contents of the articles within the newspaper; for now, take a look at the front page. Notice how much space is given to emphasize future Palestinian participation, even though they were excluded from the talks themselves. Al-Ahram — September 19, 1978 FULL TEXT OF CAMP DAVID PEACE AGREEMENT GAINS WON FOR PALESTINIANS End to military rule; Israeli civil administration in West Bank and Gaza Israeli commitment to halt all new settlement construction in the West Bank and Gaza Beginning of Israeli withdrawal from West Bank and Gaza immediately following talks Participation of Palestinian people in negotiations concerning future of West Bank, Gaza, and Jerusalem Respect for Palestinians’ lawful rights Veto power for Palestinians on any resolution concerning them [at the United Nations] Enforcement of Resolution 242 [UN resolution mandating Israeli withdrawal from Palestinian territories under a negotiated peace treaty; interpretations of the resolutions vary] in the West Bank and Gaza Basic participation in negotiations on the issue Return of displaced persons [unclear what this refers to, as the treaty does not mention the right of return for Palestinian refugees] Prompt solution to refugee problem [again, unclear] GAINS WON FOR EGYPT Israeli withdrawal from all of Sinai to international borders Immediate withdrawal to begin within three months following signing of peace treaty Return of all Israeli airports in Sinai to Egypt, at which time they will become civil airports [United Nations] Security Council guarantees the agreement and safe borders for Arab countries and Israel [unless I am interpreting this incorrectly, this is false; the UN General Assembly rejected the Camp David Accords because they did not guarantee the right of return for Palestinian refugees, and I cannot find evidence of Security Council approval of the agreement] Egypt will only implement agreement if Knesset approves withdrawal from settlements SADAT IN MESSAGE TO EGYPTIAN PEOPLE: I GOT WHAT I WANTED AND WE WILL NOT HAVE TO SEND OUR SONS TO WAR AGAIN Widespread reactions across the globe: Washington: A victory for world peace London: The conference exceeded all expectations Israel: The agreement defies belief Ali Hamdi writes from Washington (Page 3) Text of conference documents and annexes p. 5 Inside this edition: Full text of conference documents p. 5 Worldwide reactions to the agreement p. 7 Timeline of events at Camp David p. 7 What they're saying about the agreement p. 7 Presidents’ statements after signing agreement p. 9 Sadat addresses the Egyptian people p. 12 Thank you for reading, and please leave your comments below!  Ready to cringe? Take a look at this excerpt from an English translation of the Jordanian penal code: "Article (2) Phrases and words contained in this Law have meanings assigned to it below unless evidence shows otherwise: ... The word (wound) means: every cut or slash which gashes the external human body tissues. For the purposes of this definition a tissue is considered to be external if it could be touched without the need to cut slash any other tissue." If you are a discerning reader, you probably noticed several errors in this excerpt. The translator has used parentheses as they are used in Arabic - to indicate proper nouns - resulting in an awkward overuse of this punctuation common in poorly translated documents. They've used the word "it" to refer to "phrases and words", which is of course plural. The term "evidence" is used incorrectly here. And of course there is the use of the noun "cut" as a subject for "gashes", when only the sharp object itself can gash, and the use of "cut slash", perhaps a sloppy edit. I don't point out these phrases to mock or shame the translator, who is anonymous and who surely was just trying to get through a job without the opportunity to get feedback from a qualified editor. I'm highlighting this because it is uploaded to a Jordanian government website, that of the Anti-Human Trafficking Committee.* This may be considered a semi-official translation and is actually one of the only partial translations of the penal code that exists on a Jordanian website. If you were translating something that quoted the Jordanian penal code, and you did a little research, you would find this existing translation. This is why I put "official" in quotes above - sometimes it's not entirely clear whether this is the official one, or just the only one! Why do official translations matter? One cardinal rule of translation is that consistency must be preserved. A certain term should be translated the same way whenever it occurs in the document, unless the context changes its meaning or it absolutely must be altered for fluency. This is perhaps especially true in legal texts. In a document where certain terms actually have legal significance, it's important not to mix them up. Perhaps "murder" entails a certain punishment but "killing" or "homicide" are more broad terms. If you know that the text is referring to homicide, it would be legally significant to occasionally translate the same word as "murder"; the reader will think the terms are distinct in the original and may act upon the legal distinction. This is a straightforward concept when we're talking about terminology within a document. But what about terminology between documents? What if I'm translating a text that quotes Article 1 of the Jordanian penal code, and the official translation is what was quoted above? Do I copy it? Theoretically, the consistency principle still holds. Your reader is probably not going to just use your text; they likely are working with other resources to understand a topic. Since the point of translation is communication, you want to give your reader as much information as possible, including that what they read about elsewhere is referring to the same thing that you're discussing. If you see this agency, the Anti-Human Trafficking Committee, mentioned in your text, but you translate it as the "Committee to Combat Human Trafficking", you are misleading your reader. A reasonable person would assume that if it has a different name, it's a different thing. So, in general, if there is an existing translation, you want to match it. The one that holds the most weight is generally the official translation, or at least the one posted on the government website. Easy, right? But what if the official translation is... terrible? Arab countries are pretty notorious for having sprawling bureaucracies. A certain government I often work with texts from has a plethora of commissions, committees, departments, etc. Every one of these entities will probably be handling their own translations. Some of them may hire excellent translators; others may allocate less budget to this task and hire the least expensive option. Again, I struggle with whether to call these translations "official", but they are sponsored by the government in some way. I actually know this to be the case because I worked on the annual reports of two ministries from the same country last year. One was a very involved project with several rounds of translation and editing done by a team of translators and graduate students, all native English speakers. The other was a task I received with a very quick turnaround time to edit a non-native speaker's translation of the ministry's report. The text I got was riddled with errors, and to make it sound natural, I would've had to rewrite the whole thing. I did my best with the time allotted and sent back an acceptable document, as was my job, but certainly nothing exemplary like the report for the other ministry. The one thing these two ministries shared was a commitment to using existing official translations of terms and phrases. But because of past work like that of Ministry #2, a lot of the existing translations were simply awful. They didn't convey the correct meaning or were grammatically nonsensical. Sometimes, one entity would have multiple official translations present on their own website! I won't give any examples here, because I'm not fond of picking apart the flaws of past or potential employers, but what resulted was a real conundrum. Should I copy the existing official translation, to preserve that all-important consistency? Or should I change it to be more readable and correct? Both are key principles in translation. Which takes precedence? Communication is key I mentioned above that the point of translation is communication. Among all the details of translation theory, I've honed in on this concept in practice to guide my decisions when I'm actually translating. I can't possibly give the reader all of the information (here I mean not just facts but also style and emotions) present in the original. But I'm trying to get as close as I possibly can. One surprising way to do this is to focus on the opposite: don't confuse the reader! If something is odd or distracting, this may hinder the communication process. On the other hand, if they can't match terms from your text to terms from an official source, you are not giving them all the information they need to use your translation in a functional way. Regarding official or quasi-official translations, the best approach is to consider the terms and phrases on a case-by-case basis. Consider the best way to avoid "translation loss" and confusion while optimizing the amount of functional information the English reader receives. With the actual names of government agencies, the value of the reader knowing that you're referring to a certain entity far outweighs the information they might gain from readability. A reader may be expected to understand that translations of names can be wonky, and could possibly already be translated. For practical purposes, that communicating that consistent information is more important. However, for official translations like the one quoted above, there is much less reason to copy the translation in use, especially if there are blatant grammatical errors. Perhaps sticking close to it is advisable so the reader knows they're the same document if they see them side-by-side, but distracting errors will hinder the communication you're going for. All of the issues I mentioned in the introduction are things I would change if I was quoting the legislation in my own translation. There are some gray areas, like if the name of the entity really is blatantly incorrect (so bad that the reader can't tell the purpose), or if it's something like a slogan. Sometimes, well-meaning legal drafters even write in English translations of certain terms - especially in the definitions section - that may be completely wrong. In each instance, I would decide what information is most valuable to communicate to the reader, and what can be sacrificed to get them that information. As a last resort, if the unclear official translation and your clear rendering are both equally important, a translator's note can be used. Of course, I always ask my client in the event of any uncertainty. You never know if the purpose the text is being used for makes some sort of information crucial and something else irrelevant. Thank you for reading! If you've made it this far, please leave a comment below with your thoughts, and connect with me on LinkedIn. I always love hearing from new people! *http://www.ahtnc.org.jo/sites/default/files/penal_code.pdf

Tur Abdin: a unique cultural milieu Last week marked a milestone in my translation career as I completed my first book translation. I was very fortunate that the work I was translating was especially interesting and educational to me personally. I would like to share some insights I gained from working on the book and what conclusions we might draw from this authentic and personal work. This book tells the story of a war fought in the late 19th century between the Assyrians (aka Syriacs), allied with the Ottoman Empire of which they were loyal subjects, and some Kurdish warlords who had taken over a historically Assyrian area of Mesopotamia known as Tur Abdin. These Kurdish tribes, unlike the more indigenous Kurdish communities that had lived alongside the Assyrians for generations, held religious and ethnic animosity for the Assyrians and subjected them to dispossession and displacement. They were also autonomous from the larger Ottoman Empire. So, from the outset we have a very unique ethnic/linguistic/religious milieu being discussed here. We have the Assyrians, a Christian population assumed to be descended from the earliest inhabitants of Mesopotamia, the Arameans. We have the Muslim Kurds, whose language is not really discussed in the book, but who are clearly differentiated into different communities (neighbors and conquerors). Then we have the (mostly Muslim) Turkish rulers and officials of the Ottoman empire who are helping the Assyrians against the Kurdish invaders. Finally there is the glaring fact that the book is written in Arabic, the language that most Assyrians speak now after the Assyrian Genocide and displacement during WWI. Shared religious language It is a common idea that Arabic-speaking Christians and Muslims use different terminology to speak about their religion. However, when reading this book, I found quite the opposite. Words I had learned in specifically Islamic contexts were used here for Christian practices entirely naturally. The passage above includes several salient examples: صلاة salah = ritual/congregational prayer Commonly used for the 5 daily prayers of Muslims, but here used to refer to morning church services الله تعالى allahu ta'ala = Almighty God Possibly the most common form of referring to God in Islam. Here used in exactly the same way by Christians. نصر nasara = to make victorious One of the names of God in Islam is nasir, "the one grants victory". In general I would associate the verb with granting Muslims victory, but this may be just due to lack of exposure to writing by Christians. ناشد nashada = to implore This root also produced نشيد nashid, "song, hymn, anthem" often used in a religious sense in Islam. في سبيل قضيتهم fi sabil qadiyatihim = for their cause This phrase was repeated throughout the book and struck me as similar to the common Islamic phrase في سبيل الله, fi sabil allah, "for the cause of God, on behalf of God". This is used in various Islamic contexts including doing good deeds or dying as a martyr in battle. This pattern of unexpected similarities continued throughout the book. It caused me to reflect on why I associate so many of these words with Islamic contexts and was surprised to find them used by Christians. Is it something about how I learned Arabic? Is it simply because my exposure to Islam is greater due to the cultural dominance of Islam in the Arabic-speaking world? I can't say for sure, but this book challenged my preconceived notions about non-Arab and non-Muslim minority communities. Diversity and respect in the Ottoman Empire It is a well-known stereotype that the Middle East is full of various religious and ethnic groups fighting one another for land and power. Some people who oppose this harmful view will promote an equally simplistic one: ethnic and religious groups have lived alongside each other for centuries in total peace and harmony, especially in the Ottoman Empire. Of course, this lacks nuance and disrespects the real historical struggles of minorities in the Ottoman Empire, many of whom were subject to systematic kidnapping of their children for forced conscription in the devshirme system. The Ottoman Empire also levied a tax against its non-Muslim subjects, which has been justified by comparing it to the alms collected from Muslims, but which many considered a form of systemic discrimination. One of my favorite aspects of this book was the way it used clear language to describe the varied experiences of minorities in the Ottoman Empire. The characters have candid conversations about religion and ethnicity. Consider the following passage, which discusses whether the Assyrians should be worried that local Kurdish communities will join the warlords and take up arms against their neighbors: لقد صدقت يا كوو، ولكن هناك مأخذًا واحدًا عليهم، إنهم متعصبون. يتمسكون بالدين، ليس حبًا بسمو مبادئ دينهم، ولا حبًا بالقيم الأخلاقية التي يدعو إليها كتابهم الشريف، بل حبًا بالحقد والنقمة والتشفّي من أناس يعتبرونهم أعداء دينهم الحنيف. ويتهمونهم بالكفر، بخلاف ما يدعو إليه القرآن. وإذا كان مثل هؤلاء المسلمين مؤمنين بحق، حسب رسالتهم السماوية، لما اعتبرونا نحن السريان، أعداؤهم ودعونا كُفارًا. لذلك إني لا أثق بأناس يتمسحون بدين سماوي، يدعو إلى الرحمة والمحبة والتسامح والغفران، وهم يخالفون جوهره وقدسيته. فلتكن عيوننا مفتوحة تراقبهم عن كثب، ونُحصي عليهم تحركاتهم. فإذا اكتشفنا أنهم يمدون يد المساعدة إلى أبناء عرقهم، من الأكراد الأغراب، هاجمناهم في دورهم وأسرناهم. “Gawvo, I believe you,” said Safar Agha, “but they have one fault: they are fanatical. They are devoted to their religion not out of love for the noble values or the moral principles called for in their scripture, but out of malice, to satisfy a thirst for revenge against people they consider enemies of their orthodox faith. They accuse their enemies of being infidels, even though the Quran says not to. If Muslims like these believed in what is right, according to their own heavenly message, they would not consider us Syriacs their enemies or call us infidels. I don’t trust people who grovel before a sacred religion, asking for blessings, love, and forgiveness, all the while acting against its ethos and sanctity. Let’s keep our eyes open and watch them carefully, keeping track of their movements. If we discover that they are lending a helping hand to the foreign Kurds, their distant relatives, we will attack them in their homes and take them prisoner.” [Upon further reflection, the leader admits that their closest neighbors are unlikely to betray them:] حافظوا على حق الجوار، وراعوا الأماكن المقدسة الواقعة في منطقتهم. فلم يسيئوا إلى السريان المتواجدين هناك. بل بالعكس، فقد كانوا يدافعون عنهم ضد الأكراد الذين كانوا يحاولون أن يغزوهم، أو يُشردوهم بعد أن يغتصبوا أراضيهم. "They’ve protected the rights of their neighbors and taken care of the holy places in their area. They never insulted the Syriacs located there. On the contrary, they defended them against the Kurds who were trying to raid the holy sites or steal their land and expel them." The leader of the Assyrians both exhibits great respect for Islam as a religion and great derision for people who use it as justification for any sort of crime. He then acknowledges that different groups of Kurds have treated them differently and some have been excellent neighbors. In another passage, the author recognizes the diversity of the Ottoman Empire and the delicate political landscape they must navigate: وفي غداة اليوم التالي، وفي موعد صلاة الصبح، دّق ناقوس بيعة مار يعقوب دقات قوية متواصلة، إيذانًا بالصلاة. امتدت أيدي السريان إلى جبهاتهم ليرسموا إشارة الصليب، إعرابًا عن شكرهم ووفائهم لمخلصهم يسوع المسيح الذي أنقذهم من جحيم المعركة ونصرهم على أعدائهم. لقد لاحظ السريان أن عددًا كبيرًا من الجنود العثمانيين وضباطهم قد ركعوا عند سماعهم دقات الناقوس، ورفعوا عيونهم نحو السماء، وطرحوا إشارة الصليب على جباههم وهم يسبحون ويمجدون الرب، استغرب السريان من حركتهم تلك، وظنوا بأن الجنود النظاميين إنما قاموا بتلك الحركة إما تقليدًا أو سخرية. ولم يدروا أن العثمانيين قد بسطوا نفوذهم وظل إمبراطوريتهم على سدس العالم. وأن ثلث سكان ممتلكاتهم يدين بالنصرانية. فلا عجب إذا ركع جنود عثمانيون ليؤدوا بدورهم الصلاة في الميدان، ويشكروا خالقهم على منته ورعايته ورحمته. كان بين الجنود العثمانيون عدد من النصارى. ربما أخفى القادة مذهب جنودهم عن الناس، لئلا يتهموا بأن في مساندتهم للسريان، إنما يشنّون حربًا دينية، مع أن الغاية من مجيئهم إلى مديات لمناصرة السريان، لم تكن حبًا بمناصرتهم، بل تثبيتًا للسلطة في المنطقة. وتحرير الأراضي الواقعة تحت النفوذ العثماني، من الدخلاء أو الثوار والمتمردين أو الطامعين. The next morning, the loud bells of Mor Yaʿqub Church rang out continuously to announce it was time for the morning prayer. The Syriacs put their hands to their foreheads to make the sign of the cross, expressing their gratitude and loyalty to their savior Jesus Christ, who saved them from the hell of the battle and granted them victory over their enemies.

The Syriacs noticed that many Ottoman soldiers and officers had knelt upon hearing the church bells ringing and lifted their eyes to the sky. They made the sign of the cross on their foreheads while exalting and praising the Lord. The Syriacs were shocked to see them making that sign, and they thought that the imperial forces did so either to imitate them or mock them. They did not know that the Ottomans’ influence extended far and wide, their empire covered one-sixth of the world, and one-third of their territory’s inhabitants were Christian. So it was no wonder that the Ottoman soldiers knelt to pray in the square and thank their creator for His blessing, guidance, and mercy, because there were some Christians among the Ottoman soldiers. Perhaps the commanders hid their soldiers’ affiliation from the others so that their support for the Syriacs could not be interpreted as intended to start a religious war. The purpose of them coming to Midyat was to support the Syriacs, not out of love for their Christianity, but rather to entrench their authority in the region and liberate the lands located under Ottoman influence from intruders, revolutionaries, rebels, and greedy people. This passage really demonstrates how complicated communication was for these populations. The Assyrians were relying on the Ottoman army for help in what they saw as a holy war, but they were also aware that not all Ottomans were exactly friendly to Christian minorities. At the same time, they were ignorant of the fact that there were actually Christians in their ranks. It had deliberately been hidden from them for political reasons. The layers of identity and culture here are not so simple as "they've been fighting each other for millennia" or "they've always lived in peace". That's it for this post - thank you for reading, and please let me know your thoughts in the comments. In recent days we have witnessed racial violence in Jerusalem as Israel attempts to expel families from the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood. As a translator, I have been intently following the language used to describe these events in English. The language that my readers know determines how they will understand my translations.

Unfortunately, I have been disappointed yet again. Despite the greater understanding of state violence since the BLM uprising of summer 2020, Americans still seem intent on using the word "clashes" to describe the interactions between heavily militarized Israeli police and unarmed Palestinian protesters. Moreover, most articles use the passive voice when describing Israeli violence ("Palestinians were injured by rubber bullets" - "violence erupted") and active voice when describing Palestinian actions ("Palestinians threw water bottles"). Why does media coverage matter to translators? As in many professions, translators are often urged to leave politics out of their work. We are here simply to convey meaning; we have no stake in the content itself. I agree in principle. Translators should never alter the meaning of a text because of their personal political or other convictions. That would be completely unprofessional and wrong. The issue here is how translators can best convey meaning to an audience that has little deeper understanding of the larger context. To truly give our readers the meaning of the text, they must know more about the reality of the situation than they are likely to know already. Our readers' knowledge is mainly based on their media consumption. We have obvious limitations on the extent we can explain meaning. Translators may not write long footnotes explaining the history of Palestine and ethnic cleansing every time they are translating something written by a Palestinian. Not only would this be cumbersome to the reader, but it could easily slip into editorializing. Many would argue this is simply not our responsibility. Nevertheless, translation is basically an endless array of choices. Which English word would best represent the meaning of the Arabic word? What did the Arabic speaker mean when they said or wrote this? What exactly were they trying to communicate? And here we run up against the question of how much our English reader knows. It is unavoidable. American coverage of Israeli violence In the current situation in Jerusalem, most Americans have seen headlines like: Hamas fires rockets into Israel after Jerusalem clashes leave at least 300 Palestinians injured (Washington Post) Violence in Jerusalem Wounds More than 300 Palestinians (NPR) Rockets fired into Israel as tensions in Jerusalem boil over (NBC News) Beefed-up Israel police clash with Palestinians in Jerusalem (AP) The content of these articles is not very different; I won't spend space here discussing it. It is sufficient to note that the words "clashes" and "violence" are often used to efface Israeli agency. Very few articles say directly "Israelis attack Palestinians" or something similar. There is very little context included in these news articles. Most Americans will read them and remain unaware that only Israel has police in Jerusalem, only Israeli forces are armed, only Palestinians are expelled from their homes, and only Palestinians have the right to live in these homes under international law. Nor will Americans learn from these articles how Palestinians have been expelled from their homes for generations, and that most Israeli cities were once Palestinian villages in the same precarious situation as Sheikh Jarrah is now. They will not know that East Jerusalem was illegally occupied in 1967 and Palestinians there are essentially stateless. They will not know that the reason for the protests is that an Israeli court awarded ownership of Palestinian homes to essentially random people based solely on the fact that these new occupants are Jewish. At least one of these people is actually American. How media coverage affects translation choices Given this coverage, we cannot expect our readers to know the full context of the Israeli occupation of Jerusalem. Let's look at some examples of how this complicates our work. لن نرحل We will not leave This is a common slogan of Palestinian resistance these days. But what does it really mean? An uneducated reader may think that it is simply one side's persistent demand to the land. Both sides probably say something like this, so what's the difference? In fact, this is a reference to the history of dispossession that Palestinians have experienced for more than 100 years in their native land. The related word ترحيل means expulsion or forced migration. Both sides may claim the land for themselves, but the contexts are completely different. How can we convey this essential history to our reader? Perhaps: We will not be expelled We will not leave our homes Our dispossession will not continue Do these indirect, explicative translations actually convey the meaning of the phrase better to an uneducated audience, or are they so far from the literal meaning that they are unjustified? قاوموا Resist! A Palestinian poet was arrested several years ago for using this word in a poem because Israeli authorities claimed it was inciting violence. Among Palestinians and other Arabs, it is a normal way to encourage any form of resistance to oppression. However, our English readers will not be aware of what, if anything, Palestinians may be resisting. Remember that news articles often say that "Palestinians were injured" without mentioning who injured them. They will describe violence "erupting" without explaining who has the power to commit serious violence - who has weapons, for instance. There are some alternatives that may give more context, such as: Fight back! Resist oppression! Don't give in! As always, the question remains whether these translations are justified because they convey the overall meaning and context better, or whether they stray too far from the source text. اليهود Jews This is perhaps the most difficult and contentious word to translate when it comes to Israel and its treatment of Palestinians. In the US, bringing up someone's religion or ethnic background when you are criticizing them is rightfully seen as bigoted. What does their identity have to do with it, anyway? Why fall into stereotyping? Surely they aren't doing anything wrong as Jews, so the inclusion of this detail is irrelevant at best and anti-Semitic at worst. However, the situation in Palestine is different, historically and legally. For example, in Sheikh Jarrah, the Israeli court has awarded ownership of homes that have been owned and inhabited by Palestinians for generations to Jews. Not because they own them. Because they are Jewish. Their religion and ethnicity is actually the crux of the issue. This is not an isolated incident; it is at the core of Israeli policy and the ideology that drives it, Zionism. Throughout its history, Israel has defined itself as the "Jewish state" and acted accordingly, discriminating against non-Jews. Therefore, when a Palestinian says her home has been stolen "by Jews" or that "the Jews are committing crimes", she is not bringing up their identity to criticize their religion or endorse harmful stereotypes. She is stating the reality of what is occurring with relevant terminology. English readers will likely not know how much of Israeli policy is based around discrimination in favor of Jews, nor will they be familiar with the ideology of Zionism that is based on supremacy of one ethnoreligious group. Media coverage refers to them as Israelis, not Jews. So, how should we translate Palestinian discussions of Jews? Some translators resort to using Israelis or Zionists whenever اليهود is used in Arabic, in order to dispel any notion of bigotry among Palestinians. The problem is that these are inaccurate; those terms exist separately in Arabic and describe different concepts. There are Palestinian Israelis that would not be allowed to occupy the homes in Jerusalem, because they are not Jewish. Likewise, the court has awarded the occupiers the right to live there because they are Jewish, not because they subscribe to a specific ideology, like Zionism. Other solutions include: Israeli Jews Jewish occupiers Jewish settlers Yet again we are caught between explaining what the Arabic speaker or writer meant and translating what they literally said. There is no easy answer here. Final thoughts Translation is more of an art than a science. We have some hard and fast rules: no personal opinions, no long explanations, no unnecessary additions or omissions. Yet we are left with many subjective choices. All of us have decisions to make in what we want the goal of our work to be. Do we want to educate our audience, or simply give them the tools to educate themselves? Are we responsible for how our audience perceives the author of the source text? How much is too much to expect of our readers? Personally, I've learned more from educating myself about unfamiliar political situations than from seeing explicative translations. However, not everyone will take the time to learn more about the context. This is part of why I write this blog, and why I think more analysis is needed in translation work. Let's at least show people how complex and demanding our task is. [This is the third article in a series of translations of Egyptian newspapers from the 1960s. To view the other posts, please click on "blog" above.] In 1961, Egyptian movie star Omar Sharif played handsome and sensitive Ibrahim Hamdy, an unlikely resistance fighter on the run, in the hit film في بيتنا رجل, There's a Man in Our House.  Book cover of Ihsan Abdel Quddous' "There's a Man in Our House", 1954. Book cover of Ihsan Abdel Quddous' "There's a Man in Our House", 1954. The film is set before the Egyptian revolution, when Egyptians were suffering under British occupation. After escaping from prison, Ibrahim takes refuge in the last place the police would think to find him: the home of his shy, nerdy classmate, where he lives with his parents and two sisters. As the completely apolitical family gets unwillingly embroiled in the brutal crackdown of any and all dissenters to British rule, they are radicalized by the experience and come out of it genuine nationalists. One of the sisters falls in love with Ibrahim, who dies attacking a military base at the end of the film. The film - dramatic details aside - is based on a true story. It was an adaptation of a 1954 novel by Ihsan Abdel Quddous, who retold the story he received in letters from the real-life Ibrahim, a man named Hussein Tawfik. Tawfik assassinated an Egyptian ally of the occupation, Amin Othman, in 1946. In the book as in the film, Ibrahim dies a martyr for the cause of liberation. But the real-life Hussein Tawfik fled the country after his escape from prison, returned to Egypt after the revolution, and was very much alive when Omar Sharif played him onscreen. I knew all of this before I picked up this newspaper from January 1966, which is why it surprised me to see an article about "the Hussein Tawfik case". Just five years after being portrayed as a hero in a hit film, Tawfik was in prison, and the state-owned press was portraying him as a self-aggrandizing "wicked person" and an enemy of the revolution. What happened? Hussein Tawfik, or the real-life Ibrahim HamdyIt's interesting to note that there is not even a Wikipedia page for the real-life person at the center of this story. Even the Arabic pages for the book and the film about his life doesn't mention his name. So who was the real person behind this famous story? And why has his real life been left out of so many sources, even while some call him the "most famous political killer in Egyptian history"? According to the sources available on the internet, Tawfik's life (1925-1983) was even more eventful than what was portrayed in the short timeframe of the book and movie about him. But he also had a drastically different personality. If you've read the book, you know the great lengths Abdel Quddous goes to to portray "Ibrahim" as a shy, modest character. For example:

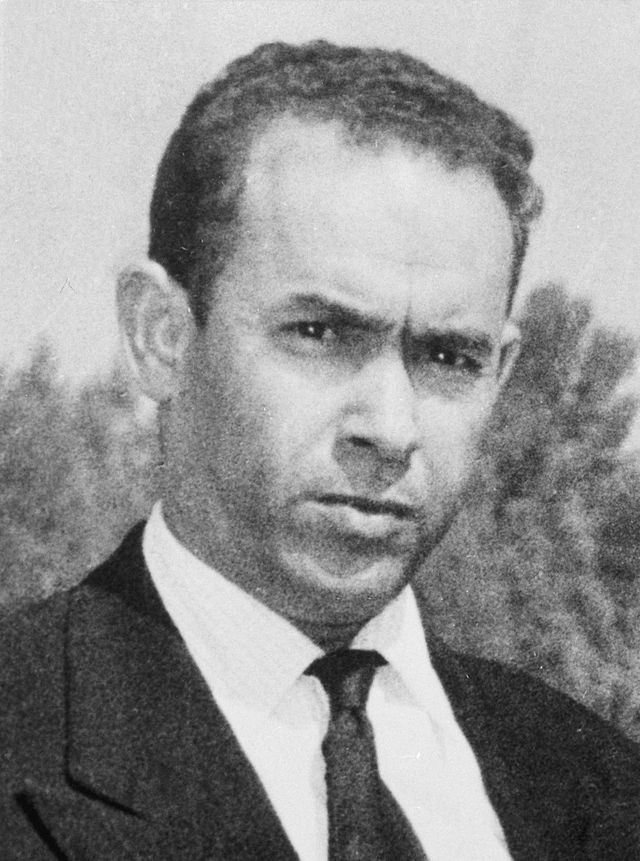

Hussein Tawfik, date unknown. Hussein Tawfik, date unknown. It's my guess that this is a description of the fictional Ibrahim more than it is of the real-life Hussein Tawfik. The first clue is that Tawfik was not an unaffiliated assassin without specific political allegiances as he's portrayed fictionally. According to the best sources I can find online, Tawfik did found his own secret society, but it may have been affiliated either with the Egyptian monarchy or with Egyptian Nazis/fascists. (The Third Reich ran a rather successful propaganda campaign in countries occupied by British forces.) The Muslim Brotherhood also may have helped him flee the country. The second insight into Tawfik's real personality is his lifelong tendency towards grandiose operations which he personally took credit for. It's worth noting that Tawfik wrote to a well-known novelist shortly after leaving Egypt, perhaps in the hope that his story would become even more famous. Once arriving in Syria, he quickly pivoted from his supposed devotion to Egypt to trying to attacking synagogues and trying to assassinate de facto Syrian head of state Adib Shishakli. He may have joined the Arab Nationalist Movement (ALM). Was Tawfik really a nationalist, or was he some sort of terrorist-for-hire? What's clear is that after attempting to assassinate Adib Shishakli in 1950, Tawfik was arrested and put on death row. But he again evaded punishment when Gamal Abdel Nasser took over Egypt in the 23 July Revolution / Free Officers Revolution of 1952. Nasser allowed Tawfik to return to Egypt as a free man. Tawfik's affiliation with Anwar Sadat Anwar Sadat in 1936 (age 18) Anwar Sadat in 1936 (age 18) Many books have been written on the life of Egyptian president Anwar Sadat, perhaps best known for signing the 1979 peace treaty with Israel. Suffice it to say that Sadat's reputation as a normalizer or moderate belies his past as a member of a number of nationalist and extremist organizations in Egypt. In fact, "Sadat was active in many political movements, including the Muslim Brotherhood, the fascist Young Egypt, the pro-palace Iron Guard, and a secret military group called the Free Officers, which sought to liberate Egypt from British influence." Tawfik met Sadat, seven years his senior, when he had just begun his political activities. Sadat may have acted as a mentor toward Tawfik and they worked together in more than one secret society. The first chapter of Ihsan Abdel Quddous' novel seems to relate the story of Tawfik's relationship with Sadat relatively accurately (apart from portraying them as close in age):

Sadat helped Tawfik assassinate the pro-occupation minister Amin Othman in 1946 - the action that set off the story portrayed in the book and movie. In fact, Sadat was arrested along with Tawfik, who was much more famous at the time for personally firing the bullets that killed Othman. Sadat, however, was found innocent, while Tawfik was imprisoned. We will come back to Sadat later, after my translation of the article. Tawfik back home in EgyptIt's no surprise that since one of the leaders of the 1952 revolution had helped Tawfik commit the crime he had run away from, he was allowed to come back home as a free man. Not much is available in sources about the next decade or so of Tawfik's life. However, the article I'm about to translate gives some rare insight: apparently he was given a job in the bureaucracy, got married and had five children. In 1954 the popular novel based on his life was published, and in 1961 Egypt's most famous actor portrayed him as a hopeless romantic with an unshakable commitment to the revolution (lower-case "r" - the film is set before 1952, but the implication is Ibrahim's commitment to the same cause). One would think that having barely escaped prison time for a decade of militant activity in multiple countries, Tawfik would settle down. But it seems Tawfik was not satisfied, and soon landed back in prison. "The Hussein Tawfik case"Let's finally get to the reason that by the time of the 1966 newspaper I'm translating, Hussein Tawfik was a reviled criminal. In 1965, the national security service in Egypt uncovered a new secret society aiming to assassinate Gamal Abdel Nasser himself for allowing Sudan to gain independence. At its head was Tawfik. Once in prison, the ostensibly steadfast Tawfik ratted out enough of his comrades that the number of defendants in the case grew to 14, including members of his own family. (Remember that torturing prisoners was commonplace.) We finally make it to January 28, 1966. On the third page is this article, detailing the defense arguments for Defendant Number 14, the final defendant and Tawfik's father's cousin. My translation follows. Following session lasting half an hour, lawyers conclude their arguments in Hussein Tawfik case Hussein Tawfik delighted to be in trial dock because all television cameras fixed on him: defense Yesterday’s session was short, lasting half an hour, and all lawyers for the accused in the Hussein Tawfik case concluded their arguments while the court decided to adjourn until Saturday for the public prosecution’s representatives to plead their case. The session was chaired by Muhammad Fuad al-Degwy, and the prosecution was represented by Attorney-General Abdel Salam Hamed and state security prosecutor Hassan Gomaa. Two of the lawyers for the final defendant, Muhammad Yusef, made their arguments, and the third, Yusef’s brother-in-law, indicated his agreement with the other lawyers’ statements. The courtroom was packed with the defendants’ wives and relatives. The first to appear was Zakaria Salah al-Abd’s wife, who sat beside the trial dock speaking with her husband until the opening of the session. The following is what occurred at the trial: Chairman – Defense for Defendant 14, Muhammad Yusef. Lawyer – Hussein Abdel Rahman on his behalf. In the name of God and in the name of the blessed revolution[1] that has brought Arab unity to the fore. This question may arise[2] today: is today’s case one of opinion or thought? No. The case is one of corruption of opinion, and deception of thought; opinion and thought have been settled in our republic, and any departure from it is a departure from the consensus and a deviation from what is right. Our country is no longer the downtrodden country it was before the shining light of 23 July, when a new and glorious era began. As we’re on our way to a better life, “If a wicked person comes to you with any news, ascertain the truth”[3]. And who is a more wicked person than someone who renounces his patriotism and goes against Shariah? That would be the prime witness, Hussein Tawfik. The public prosecution has accused the defendant, Muhammad Yusef, of knowing of the plan to attempt a coup and of failing to report it to the prosecution. The prosecution has also said that it is requesting sentencing of the defendants under Article 96, not 87, as established in the minutes of the January 13 session. This means that the prosecution has excluded this Article and the charge of attempting to overthrow the regime no longer applies to the defendants. So, how can Muhammad Yusef be punished on the basis of knowing of the crime which the prosecution has excluded for the rest of the defendants because it cannot be established for any of them? If the prosecution, after long investigation, has excluded this charge, then how can Muhammad Yusef have known of this crime, from his first meeting with Hussein Tawfik, and failed to report it? Abdel Salam Hamed – We presented the charge that he knew of the plan to commit a crime, not that he knew of the coup attempt… Lawyer – This plan, whether a crime or not – and the plan was not a crime, and therefore whoever knew of it and didn’t report it cannot be punished. The point of reporting is that it’s a right by default, but it’s a right qualified by that the report should be about a punishable crime, not about a lawful, unpunishable act. Therefore, I request the complete exclusion of the final defendant from this charge. If we assume that he should have reported something, what was there to report, and what did Hussein Tawfik say to him for him to report it? Hussein’s father is Muhammad Yusef’s cousin. Hussein has been a deviant with an overactive imagination since he was a child, aspiring to fanciful heroics, babbling nonstop, only liking to talk about his escapades. According to Hussein’s brother Saeed, Muhammad Yusef always rebukes Hussein for what he does and how much he talks. When asked, Saeed said, “Muhammad Yusef is our relative, he’s over 70 years old, and none of us ever talked about the organization in front of him. It’d be ridiculous for us to talk about it in front of him – he’d always tell us, ‘You’re the reason your father died.’ It’d be ridiculous for us to talk in front of him because he was an important general for the political police, and he knew more about Hussein Tawfik than anyone, but Hussein never said that Muhammad Yusef knew about the organization. The last time I saw Muhammad Yusef, Hussein was there, sitting with Siyuf talking about his escapades in Syria[4], and Muhammad said ‘Guys, I’ve never agreed with what he’s done – his dad died because of this.’ This Hussein Tawfik person has accused us because he’s the witness, and all he cares about is showing off that he’s a hero even in the toughest situations. When he was questioned in the first interrogation, he started bragging about his 25-year history, that had nothing to do with the charge, starting from 1942 when he was a high school student and started the formation of a secret organization. ‘I killed 3 Englishmen and Amin Othman myself, and in the Shishakli days I formed a secret organization to unite the Arab world.’”[5] Delighted Now he’s in the trial dock, delighted because all the television cameras are fixed on him and he’s on the front pages of the newspapers.[6] Chairman – He doesn’t look it. Lawyer – I’ve been watching him constantly during recess and I’ve found a much more relaxed person than he is now… He’s conceited, he loves the limelight. In his statements against Muhammad Yusef, he said that he was so ancient that he must be in touch with the old era[7] and people from back then, who of course want to bring back the old times. These are his statements, from his point of view, not Muhammad’s Yusef’s, who served the state within the limits of his role with the political police. The question is, why did Hussein bring Muhammad Yusef’s name into this case? In my opinion, Hussein was in Sudan in 1947[8], and Muhammad Yusef was in contact with him in Sudan, as he went there often, and he saw what a bad situation Hussein was in there. So he contacted Hussein Tawfik’s father and asked him to stop helping him financially. It’s possible that Hussein wanted to mention Muhammad Yusef’s name to show that people like Muhammad Yusef were in his organization. And it’s possible that Hussein wanted to benefit from the ruling that by giving names of his partners he would reduce his sentence. Even so, Muhammad Yusef couldn’t have imagined that Hussein, who the revolution saved from Mezzeh Prison[9] and pardoned and put in a center and gave a salary that someone with a PhD couldn’t dream of – he couldn’t have imagined that Hussein was working against the revolution after all that, and after he’d become a father to five children and a husband, the sole breadwinner for his family. Muhammad Yusef served his country for 33 years and oversaw security procedures in the Palestine War against the Zionist activity that gave birth to the Arab league[10]. Does it make sense for him to stand with Hussein and the Brotherhood[11] when he was the first to warn of the danger of the Brotherhood, when he was stable in life, when his daughters were getting married and his sons were studying, when he had turned 67 – why would he join a conspiracy? This is ridiculous. Chairman – Mr. Muhammad Subh, delegate of defendant Muhammad Yusef. Lawyer – The defendant, Hussein Tawfik, thought that Muhammad Yusef hated this new era, because he had been working for the old guard. Muhammad Yusef responded to that in his statements, saying that he had retired, the state had permitted him to travel, his situation was stable, and he had no goals other than stability. The law prohibits punishment of relatives in some cases, and Muhammad Yusef is a relative of Hussein Tawfik. The wisdom of the legislature to pardon them is relevant because of the familial tie which prevents Muhammad Yusef from reporting him. His position was that of a father. He advised him not to do anything wrong, because there was no more room for that or reasons for acting this way, although he still had solidarity. Chairman – Does he mean solidarity in corruption before the revolution, which Muhammad Yusef mentioned when he said that at first there were different parties, but solidarity in corruption? Lawyer – Muhammad Yusef said that, and Defendant 1 misunderstood, his thoughts go in strange directions. I call for acquittal. Chairman – Mr. Halboun. Halboun – I agree with the plea. Chairman – With that, the defense arguments are concluded, and the session is adjourned until 10 o’clock Saturday to hear the prosecution’s arguments. [1] The revolution of 23 July 1952, also known as the Free Officers’ Revolution in English, led by Gamal Abdel Nasser and other military officers, which established independent, socialist, Arab nationalist military rule in Egypt. [2] A play on words, as the word “revolution” and “arise” (i.e. rise up) are linguistically similar in Arabic. [3] Quran 49:6, Trans. Yusuf Ali [4] As mentioned above, Tawfik escaped to Syria and resumed militant activity there. [5] Unclear where Saeed’s quote ends, as the end quote is missing in the text. Remember that Tawfik attempted to assassinate Shishakli, but he was part of an established organization, the Arab Nationalist Movement, not his own secret society. [6] This article is perhaps strategically placed on page 3. [7] I.e., the monarchy which was overthrown in the 1952 revolution. [8] This is not established in any online sources, which say that Tawfik escaped directly to Syria in 1947 or 1948. [9] Now-defunct Damascus prison which held political prisoners after the 1949 coup in Syria, presumably where Tawfik was incarcerated. [10] The War of 1948, in which Egypt and other Arab countries attacked the newly-declared state of Israel after months of ethnic cleansing of Palestinians by Zionist militias. The wording is unclear, but the lawyer probably meant that the fight against the Zionists led to the expansion of the Arab League in 1945. [11] The Muslim Brotherhood, the largest and most significant Islamic political movement in Egypt and the Middle East, outlawed at the time along with all other political parties. AnalysisThe main point I got from the article above is that the state-owned newspaper that published was more than willing to propagate the vilification of Hussein Tawfik - and that this vilification came from both sides of the trial. Notice how the defense attorney begins his arguments by insulting Tawfik both politically and religiously, before distancing his own client entirely from the primary defendant. Tawfik is also portrayed as ridiculously self-absorbed, talkative, obsessed with his own heroism, and ultimately disloyal to the revolution. It's hard to believe that this person is the same one portrayed about a decade before in a novel and film as selfless, soft-spoken, a reluctant hero setting out to assassinate the خونة , "traitors", of the revolution. Now Tawfik himself is being held up as practically the archetype of the traitor. To those not familiar with Egyptian politics it may be confusing why one accusation of an assassination attempt of an individual (Nasser) would lead to complete ostracization from the revolutionary movement. From our perspective, we may see Tawfik as continuing the revolution, fighting the next unjust regime as he did the last. Egyptian politics did not accept this logic in 1966. Nasser was the embodiment of the revolution. As the lawyer explains, public opinion on the topic is "settled": dissent is no longer necessary or permissible. Such an unyielding view of Nasser's heroism was not only imposed top-down by the state, but supported by most Egyptians; it's hard to compare Nasser's clout to any other political figure, but the closest I can come is JFK for American liberals or Nixon for American conservatives. The added twist is that Nasser was a military dictator with unbridled power to extinguish political opposition and censor the press. A linguistic note: The lawyer repeatedly referred to العهد القديم and العهد الجديد , "the old era" and "the new era", referring to the periods before and after Nasser's revolution. These vague terms sound awkward and overly dramatic in English, so I considered capitalizing them, but I don't know if they were used widely enough to justify their consideration as a proper noun. Thoughts from linguists on this issue are well appreciated. So what happened to Tawfik?Hussein Tawfik was sentenced to life in prison for the crime of attempted assassination of the president in 1966. When Nasser died in 1970, Tawfik's old comrade Anwar Sadat became president, leading some to think Tawfik's release was imminent. But Sadat declined to release his old friend, probably thinking him guilty of trying to thwart the Free Officers Movement which Sadat helped lead. There is virtually no information about how Tawfik fared in prison under Sadat's rule, or the fate of his wife and children. One can assume political prisoners were not likely treated compassionately under a military dictatorship. In 1981, Sadat was assassinated by an Islamist group, and Hosni Mubarak became president, a seat he would occupy until the 2011 revolution. For one reason or another, it was Mubarak who ended up releasing Tawfik from prison at the age of 58 in 1983. Tawfik died at his family home only months after being released. He died young, but far from heroically, after his old comrades had taken over the country and become world famous while he languished in prison. I really hope you've enjoyed this article and that I've done justice to Hussein Tawfik's eventful life. My hope is that he would be remembered as an important figure in his political context, instead of a nameless romantic played by Omar Sharif! Thank you for reading, and please look out for my next post, with more on Nasser... Sources:

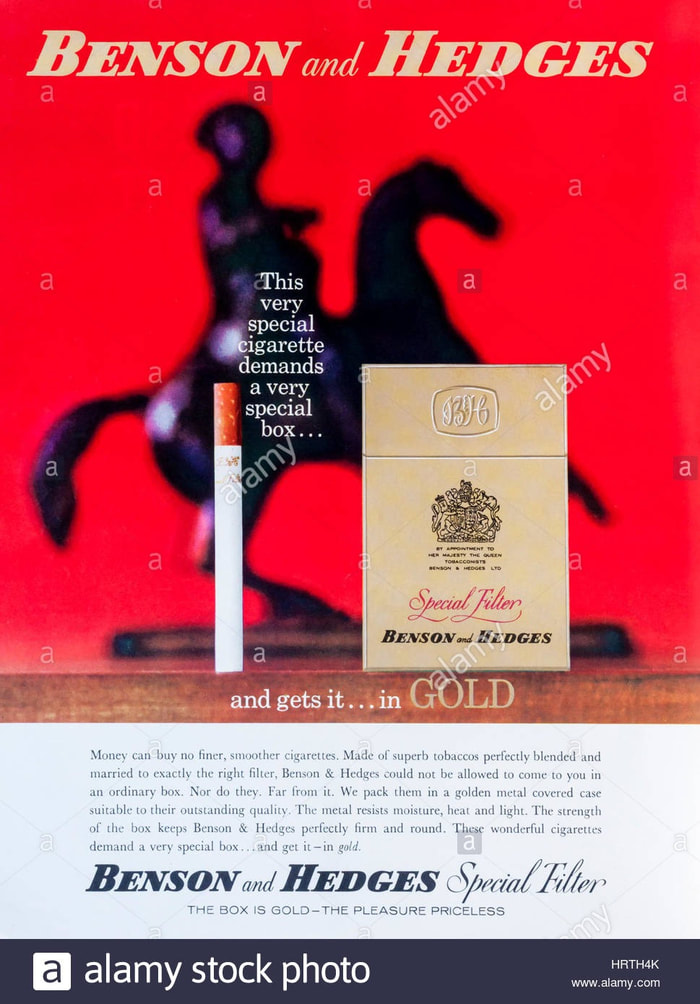

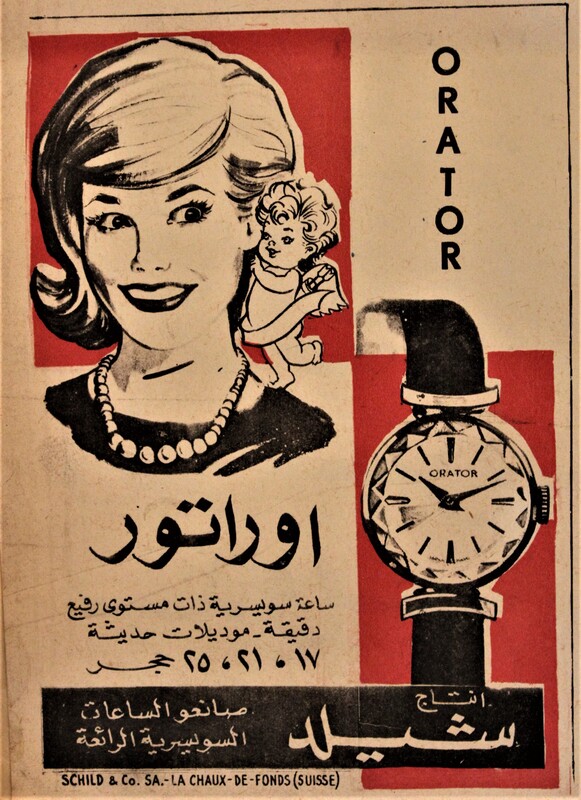

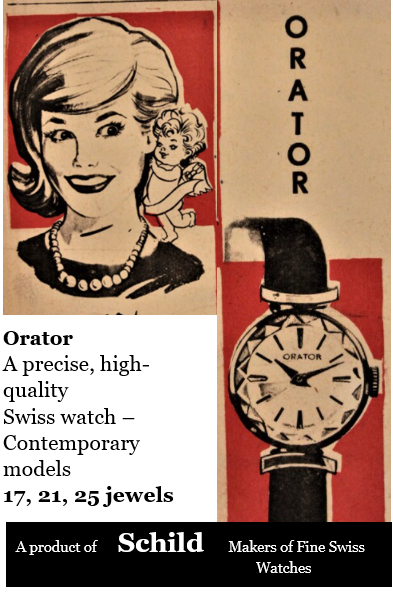

https://www.marefa.org/ https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/sadat-and-his-legacy-egypt-and-the-world-1977-1997 https://www.albayan.ae/books/eternal-books/2015-11-27-1.2515531 https://www2.bfi.org.uk/news/egypt-s-revolutions-film https://alwafd.news/ Article from Al Akhbar, January 28, 1966, Page 3 [This is the second part of a series translating articles in historical Egyptian newspapers. For other parts please navigate to the "Blog" section of my site where all the posts are listed.] Welcome to another article in which I translate articles from 1960s Egyptian newspapers. As I mentioned previously, this series is about two historical newspapers last year at the Sur al-Azbakeya book market in downtown Cairo. They were doomed to become unread souvenirs until I decided to turn them into a quarantine translation project. There's lots of interesting political content in these papers, but because I think we've had enough politics this week, here's something fun: advertisements! If you're like me, you find flipping through old ads in your own language fun - they genuinely reflect the tastes and cultural norms of the time and may even be difficult to understand based simply on outdated expressions or information. These ads come from a newspaper/magazine called اخر ساعة (Akher Saa, or "The Last Hour"), founded in 1934. Like the newspaper I drew from for my last article, it was state-owned starting in 1960 (around the beginning of Gamal Abdel Nasser's presidency). In the news and commentary articles that I'll translate later on, the political angle of the publication will be blindingly clear. Advertisements, however, are supposedly apolitical. While the newspaper would've had rules on who could advertise for what in their pages, most generally popular and family-friendly products would be able to buy ad space without a problem. Looking back, however, there are some interesting historical messages to be gleaned from the contents and imagery of the advertisements. (Please note that my formatting of my translations here is not intended as a good-quality design transposition! I simply wanted anyone reading here to be able to see where phrases were located on the page.) Let's take a look: A book giveaway by an Egyptian publishing houseThis ad, placed near the beginning of the paper, offers a free book courtesy of a major publishing house. Dar al-Maaref, or "House of Knowledge", still exists as one of the oldest and largest publishers in the Middle East. Like this magazine, it was nationalized in the early 1960's under Nasser's socialist program. Notable here is the number of stars of Arabic literature who wrote chapters for this free book encouraging reading. Taha Hussein, for example, was a prolific author and widely renowned academic famous for propagating a strain of Egyptian nationalism similar to Nasser's. Abbas Mahmoud al-Aqqad was similarly well-known, especially for his novels, his political career, and his writings opposing Nazism. A bank account at Port Said BankThis ad speaks for itself, but left me wondering why an Egyptian bank would have a branch in Somalia, and why that would be something they'd specifically advertise. Were lots of Egyptian businesses active in Somalia in the 1960s? Two very fancy cigarette brandsHere is a lesson in translation and localization. I didn't have to translate the Benson and Hedges ad, because the Arabic is itself a translation of the original English. I assume the difference in design is due to the company creating separate color versus black-and-white designs for the same ad copy. I couldn't find the original English ad for Marcovitch Black & Whites, but the writing style is awkward enough to give away that it's also a translation. Today, companies advertising in foreign countries will "localize" their marketing, instead of simply translating it. This means that they use a translation and localization company to adapt their content to the audience in whatever locale they will run the ad in. Ads run by American companies in Egypt today will use language and design they think will appeal to Egyptians, instead of whatever the ad company thought up for an American audience. But "localization" was not even a term in use until the past two decades or so, and clearly in 1966 it was not seen as an imperative for international business operations. It's worth mentioning that Egypt used to be a major exporter of tobacco until WWI. Greek-owned companies in Egypt produced cigarettes that they exported to Western countries with labels showing Cleopatra and the pyramids. (Yes, 19th century Greek-Egyptians were localizing their marketing, knowing that the exoticism would appeal to foreigners.) Middle Eastern strains of tobacco were popular enough that they inspired Western brands like Camel to design their packaging to match the "Oriental" themes of Egyptian cigarette brands, even when their products were produced domestically. By 1966, the Egyptian cigarette industry had been nationalized and then declined, and it was instead Western companies selling their cigarettes in Egypt. But clearly they made little effort to actually appeal to local people, because their ads are direct and awkward translations from English advertising copy.

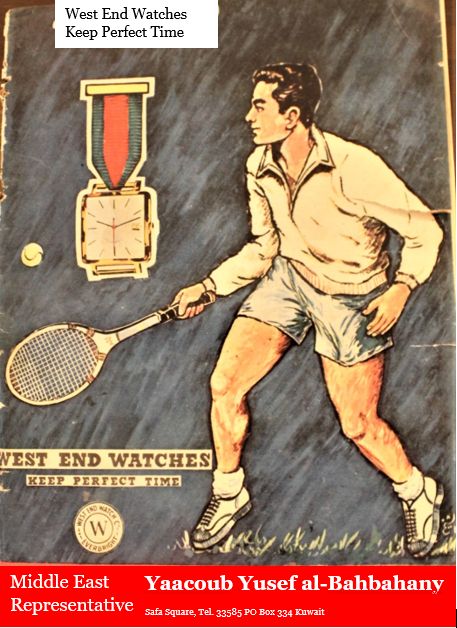

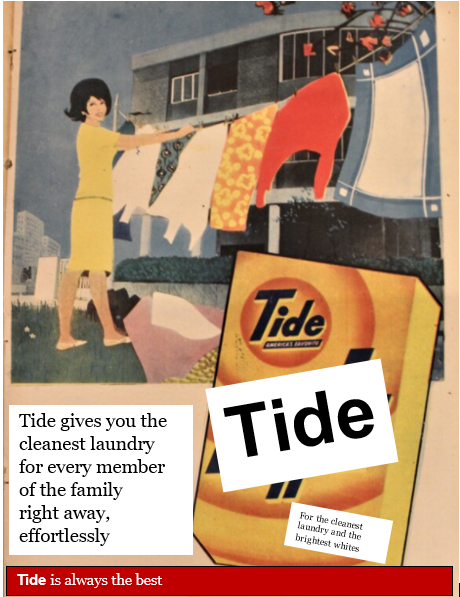

The first of these ads is in the women's section of the paper that includes articles on fashion and society. The second takes up the entire back cover of the magazine. Culturally, the appeal of these ads are a little confusing, because they show a two white (or very fair-skinned) people, one of whom is playing tennis, which isn't a very popular sport in Egypt. Again, it seems like they are direct translations from English ads, with no changes to the drawings. Tide, America's FavoriteMy favorite part of this full-page ad, part of the women's section, is the decidedly modernist building in the background. Anyone who grew up in a US city will recognize this type of building, but it's very uncommon in Egypt - at least today. Rapid development in Egyptian cities has led to much of the architecture of that period being destroyed. I wish I could know whether a house like that would've been familiar to Egyptians. I assume this was also a direct translation from English with the design preserved, but I couldn't find this exact ad online. ConclusionThese ads can teach us a few things about Egypt in 1966. Most obviously, foreign brands did not localize their products for marketing and sale in Egypt, but rather produced word-for-word translations of the ad copy they already had.